‘Redeem Team’ 1.0

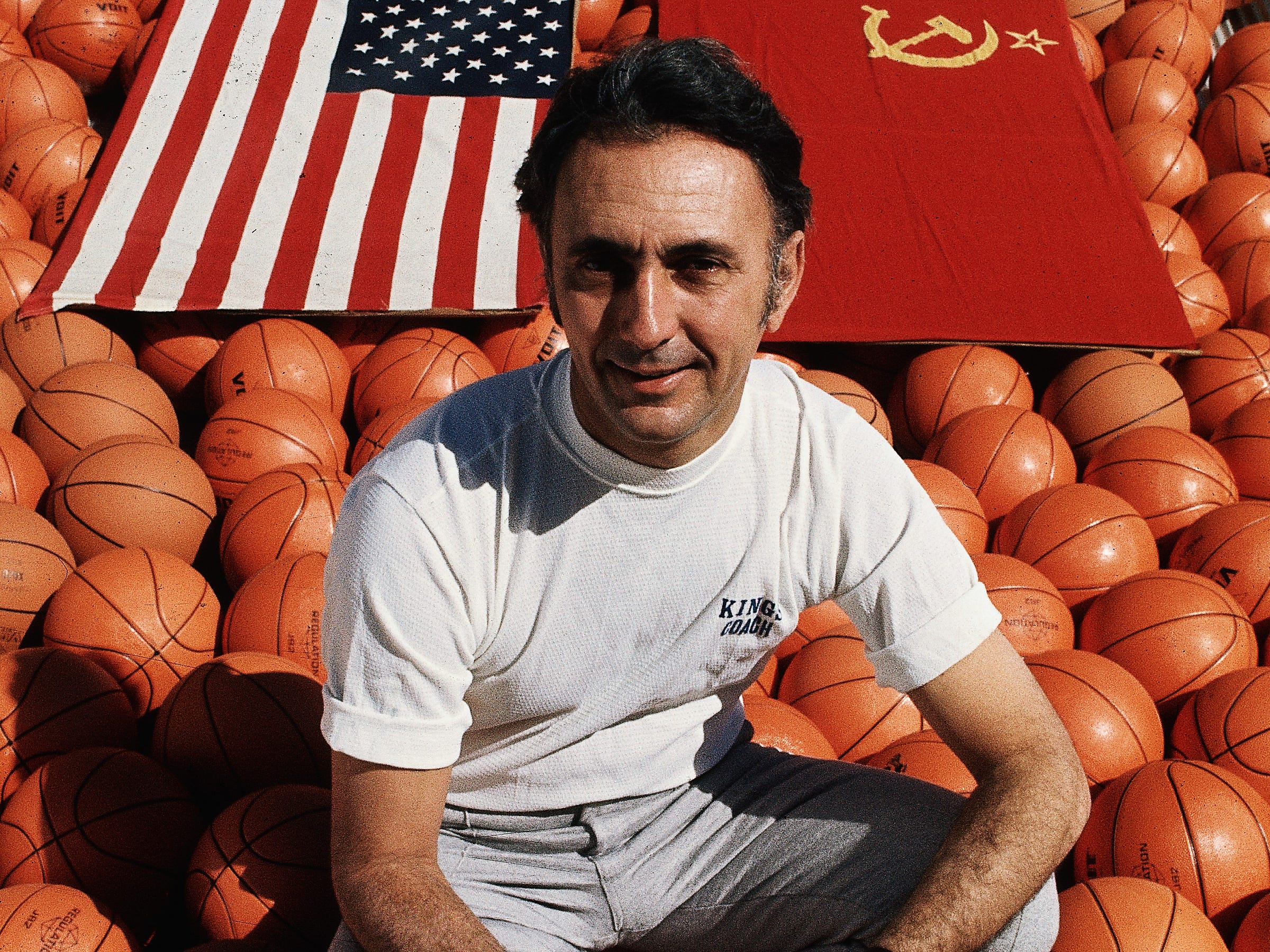

PART 2: In May 1973, a "friendly" US-USSR series turns into a war

This is the second and final part of the story. Read part one here.

BY TRAVIS MORAN

You’re reading Part Two. Read Part One here.

Almost immediately, the NCAA put the kibosh on the plans for the cross-country, six-game series, souring Marquette head coach Al McGuire, whom the AAU had invited to lead the college all-star squad. Hoping on one hand to reassemble as much of the Munich team as possible and on the other to add UCLA phenom Bill Walton, the AAU hit another wall when the NCAA then declared the series “unsanctioned,” putting the remaining eligibility of any players who participated in jeopardy.

The feud between the two organizations was long-running. Kennedy had taken a more hands-off approach to the rising t…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to TrueHoop to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.