Part 1: Daryl Morey, Rafael Stone, and the exploding Rockets

“The single raindrop never feels responsible for the flood.”

Below is the first half of a story just published to TrueHoop subscribers. To read the whole thing:

By HENRY ABBOTT and YARON WEITZMAN

Daryl Morey changed NBA basketball by replacing fragile human assessments with something more calculated. He measured everything and ultimately valued different players, coaches, and styles of play—leading to many unusual bets. For the most part, time has proven him to be brilliant: His Rockets won more than 60 percent of their games and routinely made it deep into the playoffs.

If there has been a knock against Morey, it’s that he’s lucid on creating angles and closing deals, but a little blind on things like human feelings and building trust. It has long been discussed as a “lack of chemistry,” but to many who have lived it, the shortcoming feels more profound. “Daryl Morey” says one NBA source who has known him for more than a decade, “ruins lives.”

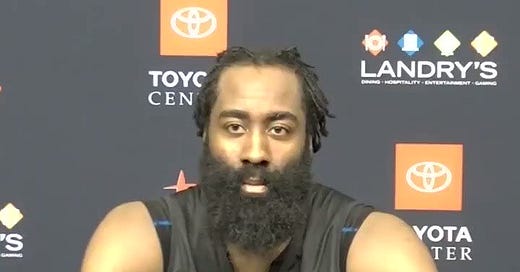

If there’s a “Game of Thrones” harshness to Morey’s Rockets tenure, it is coming full circle now on a team struggling to care enough about each other to function. Billionaire Tilman Fertitta has become the butt of jokes, and one person close to the team says he suspects they are on a path to become the worst team in the NBA. One of the team’s two best players from last season—Russell Westbrook—has already gotten himself traded. The other, James Harden, is making news almost daily for tearing at the fabric of the team by requesting a trade, breaking COVID rules, and reportedly throwing a ball at a young teammate. The team’s struggle with COVID protocols meant they are the only NBA team to date that couldn’t field sufficient players for a game—their season opener had to be postponed.

But there’s a deeper story of the Rockets’ infusion of callousness.

Daryl Morey moved to Houston in 2006, as the Rockets’ assistant GM. Like many well-to-do Houstonians, Daryl and Ellen Morey purchased a large house—theirs was near Buffalo Bayou, a drainage artery that runs away from reservoirs west of downtown. Then it started pouring. Eight to ten inches of rain flooded more than 3,000 homes in 2006. Hurricane Ike battered nearby Galveston and parts of Houston a couple of years later. In April 2009, several thousand more houses flooded, especially along Buffalo Bayou.

A house in a flood zone wants constant care and attention. Before the rain there is the upgrading and maintaining of pumps, valves, and drainage. The storms bring bouts of stress: sandbags, generators, power outages, and mucky cleanup. A few years in, the Moreys—hardly sentimental people—divorced houses altogether. They would face rain storms from a high rise in the Memorial City neighborhood. Once ubers became ubiquitous and readily available, Morey essentially quit cars, too—telling the Wall Street Journal driving was a poor use of his time. (Years later on the Rich Eisen show he explained, “I’m on my phone too much, it’s just too dangerous. For the sake of humanity.”)

And besides, many days Morey didn’t need a car at all. Another employee, general counsel Rafael Stone, lived nearby and was happy to drive Morey to work.

Morey and Stone got along fine. One Rockets employee at the time remembers them as “best friends.” In a recent Zoom press conference, Stone made a passing comment about Morey damaging his dash board with a foot on a morning commute. “Daryl and I are extremely different people,” Stone added. “We worked well together and became friends because we’re from very different perspectives but oftentimes ended up at the exact same point.”

One of Stone’s best friends, Andre Burrell, remembers Stone saying that “Daryl was really cool to him and took him under his wing, that he was getting all sorts of insights.”

Both were hired by then-team president George Postolos to bring a certain business acumen to a franchise that had long been defined by the well-liked but hardly cutting-edge Carroll Dawson.

A year into Morey’s time in Houston, Dawson was shuffled into a consultant role to make room for Morey to become general manager. It was an agreement Morey secured from then-team governor Leslie Alexander. The Rockets moved on from Dawson as easily as Morey moved on from houses and cars. That was another part of what fused Stone and Morey—an appreciation for the cold transactional nature of things. Many dream of running an NBA team. It’s a little cutthroat, at times.

Some college freshmen arrive at school unsure of what they want from their lives. Rafael Stone was not one of those kids.

Chris Jones first met Stone back in the fall of 1990. They were freshmen basketball players for Williams College, a Division III liberal arts school in leafy Williamstown, Mass. Even then, Jones—who would go on to live with Stone for three years—could tell that Stone was different. “Raf had his life planned out,” he says. “He was going to play basketball, then go to law school, then he hoped to one day be involved with an NBA team.”

Stone grew up in Seattle. His father was a corporate lawyer who had starred at point guard for the University of Washington. This was the path Stone intended to follow. He played the same position and had many of the same dreams. “He was very quick and very savvy,” says Robert Williams, another former teammate, roommate, and longtime friend, “and he looked to shoot first.”

He loved basketball, both playing and watching his hometown Sonics. He took the craft seriously but he spent most of his free time studying for his LSATs. He applied to the law schools at Harvard, Stanford, and Yale “because he wanted to get into the three best ones,” says Andre Burrell, another former roommate and longtime friend. All three schools accepted Stone. He chose Stanford. From there he landed a job at the New York City-based corporate law firm Dewey Ballantine.

Stone has remained in touch with his roommates in the three decades since. They communicate via text chains, monthly calls, and (like everyone else during the pandemic) Zoom sessions. His friends describe him as fiercely loyal, the type of person who, Jones says, “can come off a bit stand-offish at times, especially if you don’t know him, but once he brings you into his orbit, he’ll do anything for you.” For Jones, a story comes to mind, “one that gets to the heart of who Raf is.” Jones got married in 1999. The next day his in-laws held a reception at their home. The party lasted a few hours. After everyone left, Stone approached Jones’ mother-in-law. “He said, ‘Hey, I’d like to help clean this all up,’” Jones recalls. “Every time I bring up his name, they talk about that.”

Burrell recalls a different story, one he believes shows that Stone was always destined for a high-profiled gig. A few years after Stone had joined Dewey Ballantine, both he and Burrell were in Ohio for an event. They went out for drinks one night and, as these things often go, used the time to discuss their respective futures and careers. “He was always really ambitious,” Burrell says, and that night he recalls Stone talking about how he “wanted something different, that he wanted more.” Stone wound up making partner in 2005, at the age of 32. A week later, according to The Houston Chronicle, he quit. The Rockets had offered him the position of general counsel. He called his friends to share the news. “He said it was the chance to live his dream,” Jones says.

To Alexander and Postolos, Morey offered vastly more strategic thinking. Much has been made of Morey’s role in basketball’s analytics revolution—leading to an emphasis on 3-pointers and identifying undervalued players from Shane Battier to P.J. Tucker. The team made a lot of trades and won a lot of games.

In baseball, the appearance of advanced analytics is called “Moneyball.” It’s about a lot of things—seeing the strike zone, fielding with range—but, no surprise, it’s also about money. Morey entered the NBA as a consultant, advising Celtics ownership on the bottom line. His annual conference takes place at MIT’s business school. A lot of the panels are about maximizing ticket revenue or gambling analytics.

NBA lifers who grew up in gymnasiums are aware that, as a boss, Morey is thinking deal-first. Many serious basketball professionals have felt swept aside by the floodwaters of Morey’s strategy.

Morey’s crowning Rockets accomplishment was to collect sufficient picks and players to land James Harden in a trade with the Oklahoma City Thunder. Instead of tanking, the Rockets stayed competitive while scraping together trade assets through years of incremental moves that have been compared to those of a Wall Street arbitrage trader. Instead of commodities, though, the Rockets were dealing people, not all of whom relished the process. FiveThirtyEight reports that, over his time running the Rockets, Morey made more trades than any GM (other than his longtime deputy Sam Hinkie, who went on to run the 76ers).

Morey’s very first trade was for Jackie Butler and a pick. The pick became Luis Scola, a great Rockets success story. But Butler was cut before playing a game and never played again. Like every NBA player, he has feelings and an agent. There were many Jackie Butlers. Morey sent 72 players packing over his tenure.

One rival executive says he has come to avoid calling Morey with trade offers, for fear they will leak to the media. Public pressure might help Morey gain leverage to complete a deal. But the leverage comes at the expense of upsetting both organizations’ stability as players, agents, coaches, and families stress about the future.

At some point, Morey figured out a money-saving trick: Almost every NBA coach has a contract that ends in June. That’s when coaching staffs tend to be built for the upcoming season, and that’s when an in-demand assistant like Elston Turner or Jeff Bzdelik might become expensive thanks to the magic of competing offers.

Morey’s solution? Rockets assistant coaches were given deals that ended in August, when the rest of the league’s coaching jobs were filled. With nowhere else to go, they didn’t bargain too hard.

Last season, Rockets coaches did some back-of-the-envelope calculations and came away believing they were perhaps the 29th- or 30th-highest paid staff.

Morey, it has been reported, made $8 million a year by the end of his time in Houston.

The Rockets and their fans once romanticized Hakeem Olajuwon or Tracy McGrady. For a while, in the Morey years, it seemed like the new administration would substitute Shane Battier as a favorite. In 2009, Michael Lewis published the essential story of basketball’s Moneyball revolution, called the “no stats all-star,” about Battier. Battier’s geeky mind was a godsend to Morey. Unlike most players, Battier loved Morey’s fat packets of stats and used the intelligence to become a defender who knew all the percentages.

Battier solved the essential conundrum of the advanced stats revolution: How do you get the players on board? “It’s so great having Shane on the team,” Morey said in the aisle of one of his early conferences. They talked about everything. When Ron Artest was new to the team, Battier was the one who advised Morey about how to talk to him.

The forward came to be so associated with advanced analytics that by the time of the 2011 conference, a giant image of Battier (in a Rockets uniform, guarding Kobe Bryant) was the backdrop of the conference’s main stage.

What made it less romantic was that not two weeks before the conference, Morey had traded Battier to the Grizzlies for some draft picks and Hasheem Thabeet.

You have just read the first half of this story. The whole thing is here.