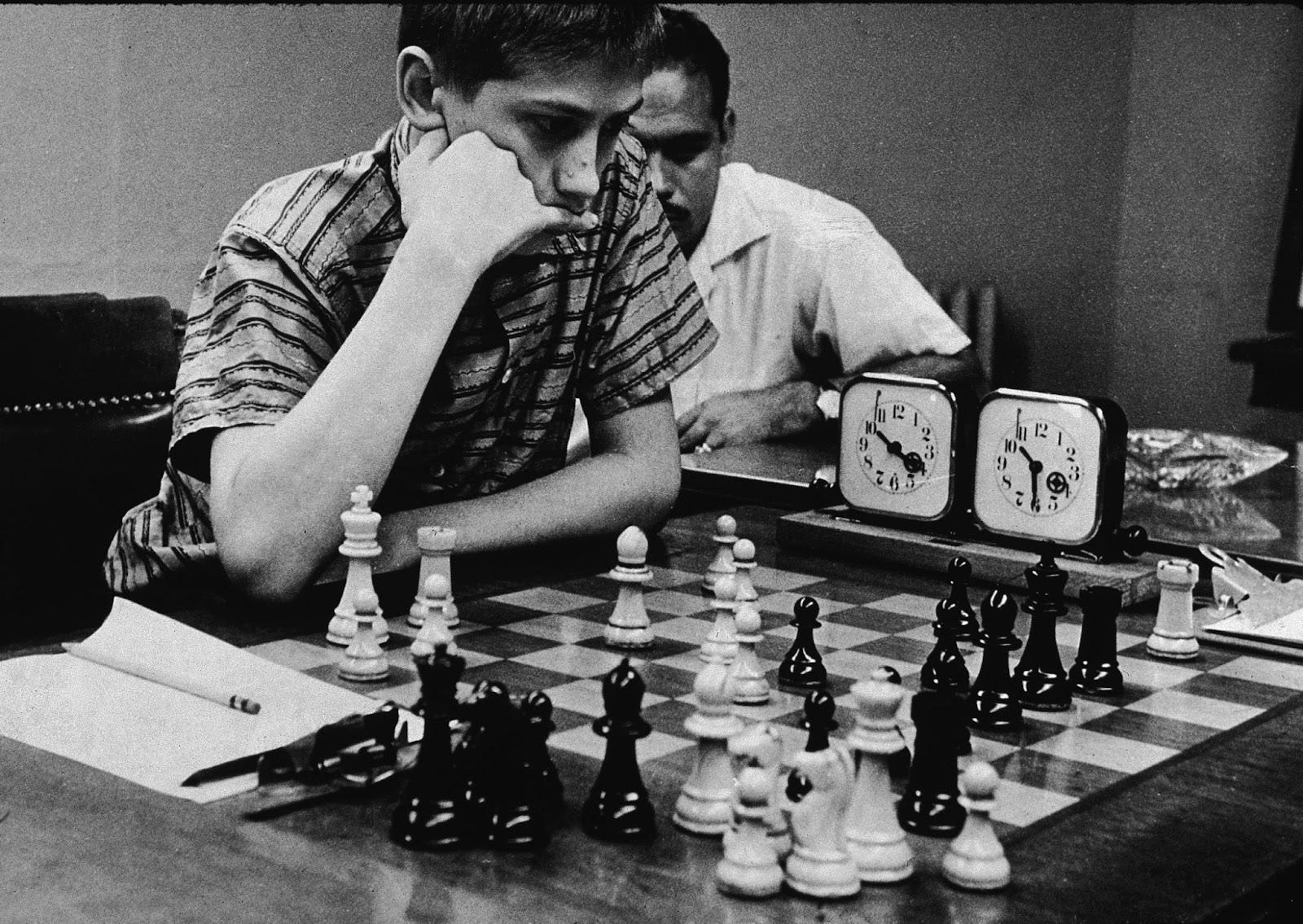

Basketball and “Bobby Fischer”

Can chess help NBA coaches unlock greater potential?

BY TRAVIS MORAN

As TrueHoop readers know, Coach David Thorpe is obsessed with untapped potential. The man (a spirit-breathing dragon, really) is an outside-the-box thinker and an enthusiastic teacher. My point is, when he calls you with an idea, already warmed up, there’s no stopping him.

So, Thorpe—a Garry Kasparov fan—hits me up one recent off-day afternoon and starts talking about chess. He’s fascinated by the parallels he sees between elite NBA players and chess grandmasters, and he has a sound hypothesis: The physical attributes of NBA players might be comparable, but top players have vastly superior pattern recognition.

“Their brains process everything at higher speeds,” Thorpe tells me. “European leagues and high-major college programs are filled with guys who are just a little slower, and their benches are filled with some players who really can’t process at all.”

Thorpe also has a film allusion for everything. In this case, his basketball mind has seized on Steven Zaillian’s grand-masterpiece of chess-themed cinema: “Searching for Bobby Fischer.” He highlights the scenes in Washington Park where young Josh Waitzkin (portrayed by Max Pomeranc) squares off against one of his mentors, Vinnie Livermore (Laurence Fishburne):

“Take a 24-second clock,” Thorpe continues, breathless. “Say I am training an NBA player who is an absolute genius when it comes to on-court speed chess. There are multiple levels to that: The speed-chess player can instantaneously recognize the mismatches; see where the opening is; decide whether he should attack via dribble, pass, shoot. I need to help him more with regular chess—how to slow down and be more strategic speed-wise as he attacks. That next level would be the ability to recognize there’s a mistake being made.”

I can picture him shaking his head and tossing up his hands now, his foot searching for an accelerator.

“LeBron and Chris Paul are so great beyond their age because there’s almost nothing they don’t recognize,” Thorpe says, “and they still have enough athleticism to take advantage. These guys are the game’s best thinkers. There’s no experience they haven’t seen and learned from.

“Basketball is all about neuroscience, Trav! Most coaches just aren’t thinking ‘big picture.’”

Coincidentally, I was about to meet another basketball coach who thinks of nothing else.

“Searching for Bobby Fischer” dramatizes the earliest competitive stages of real-life chess prodigy Josh Waitzkin. At its core, though, the film is a tale of teaching and learning.

Josh has two chess mentors with disparate, competing philosophies. His hired coach, Bruce Pandolfini (portrayed by Sir Ben Kingsley), has a classical approach: He wants Josh to master rigid self-control; to wait until he sees the patterns unfolding; and then to pounce. His other, less formal teacher, Vinnie (Fishburne), a park hustler who plays for his fix money, believes in feeling the game, forcing the action, and taking risks like deploying one’s queen early and often—a tactic that rankles the by-the-book Pandolfini.

“Searching…” tackles the chess-genius archetype more compassionately than do popular fictional takes, which tend to characterize brilliant players as disturbed and/or doped-up. (The real-life Bobby Fischer, who many believe suffered from undiagnosed mental illness, would have his own chess fame eventually overshadowed by decades of unstable behavior and ignominious outbursts.) However, these torments are routinely depicted as the tolls paid by extraordinary chess minds for access to their rare talents in visualization:

Well before the opening move, the work is underway. Multiple roads to victory have been sketched and discarded. Hundreds of schemes, thousands of permutations. Turns planned. Potholes marked. Detours charted. Damages assessed. Everything drives to that fork where the map ends and the real trip commences. Unless, of course, the opponent offers them a shortcut to victory: the mistake.

There are other players, though, who tempt fate and hazard a brasher approach: Instead of waiting for a mistake, create one. Trade some paint and force both cars off-road. Make everything loose, unfamiliar, discombobulating; then press the pace. Opponents now have to react, maintain composure, and predict—all while keeping their eyes glued to the road lest they neglect a gap in the guardrail and tumble into oblivion.

Like most games, chess and basketball fall victim to (often) obvious, yet (always) arguable juxtapositions.

“A skilled adversary is beatable when his movements are restricted and his patterns are exposed. [...] It is a ballet of the brain, choreographed on a wooden slab.”

The thing is, chess might be more than an analogy.

Having spent the past dozen years abroad, I hadn’t caught the sprawling epic of the Caltech Beavers’ NCAA-record, 310-game conference losing streak, which ballooned in both stubbornness and insanity for over 25 years; nor that their head coach, Dr. Oliver Eslinger, had revolutionized a program rostered with rocket scientists, computer engineers, and quantum physicists to break that streak. Luckily, Chris Ballard penned a fantastic piece for Sports Illustrated that US-based basketball fans probably read back in 2015. That article also mentions Eslinger’s doctoral dissertation: “Mental Imagery Ability in High and Low Performance Collegiate Basketball Players.”

Notes Ballard: “[Eslinger’s] conclusion, after studying 172 players of both genders across all NCAA divisions: Envision your performance and you can enhance it.”

When Henry Abbott asked me to review the draft of a book Eslinger had written during the pandemic, he used the phrase “eureka moments” to spotlight what had fascinated him most. In his manuscript, Eslinger—called “Doc” by his friends since he earned his doctorate in counseling and sport psychology from Boston University—chronicles his trials, errors, and eventual breakthroughs as head men’s basketball coach at Caltech.

For our first call, I asked for 15-20 minutes of Eslinger’s time. When on the phone with people you haven’t met, it’s hard to visualize them, even if you’ve seen their faces. You lack the sincerity, the verity, of expressions in real time. Sometimes that leads to reticence or guardedness. With Doc, there were no such feelings. His unslakable thirst for knowledge was captivating and energizing; within moments, I was convinced I was learning from a total genius.

Over the next two hours, we’d discuss narrative arcs and Heller’s “Catch-22,” but also philosophy, psychology, music, neuroscience, basketball, and (eventually) chess. From my end, it was an absolute masterclass on the human mind, mental imagery, and how basketball could benefit from more of both.

Among the many gems Doc gave me:

Neuroscientifically, we know the power of story, and the power of remembering things through story and song. If we can explain something through story, not only are we going to grab people’s attention more often, we’re also going to help them remember it. If you’re just directing—go here, go there—that stuff isn’t going to be encoded into long-term memory. But through story, song, and even touch sensation, you can get people to remember more. So, I’m always thinking about metaphors and analogies.

To connect all the dots, Doc shared a story from his book-in-progress:

It’s 1989.

“Oli” is a scrawny 14-year-old who has just moved with his family from Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, to the Albany (NY) suburb of Delmar. Friendless, he plays “Double Dribble” for hours. As the two-dimensional players flicker across a staticky screen, he begins to see faceless teammates and opponents all around him. He starts to hear their rubber soles chirping on the floor and feel his own legs galloping; he smells wood, leather, musk; he tastes the metallic tap water in the squeeze bottles. Those senses coalesce and catalyze a feeling: He needs to play for real.

Basketball is Oli’s passion, but as a scared, lonely outsider, it’s also his only path to fitting in and making any friends. He tries out for his freshman team at Bethlehem Central, barely makes it, then finds himself relegated to the pine. Though he finds the camaraderie he’s been seeking, Coach Pace has a right way of playing, and he expects everyone to adhere. Blame for mistakes often falls upon the players, and soon a greasy fear spills into Oli’s pure love of basketball: the fear of failure and losing his connection to the game, but even more than that: the fear of wondering how he will survive here if it’s suddenly gone.

Before family and friends, Oli gets some playing time. He makes a steal and goes on the break, one-on-three. Years later, when he becomes a coach himself, Oli will recognize Coach Pace’s words in his own voice—Wait for your troops! Wait for your troops!—but he sees an open shot, pulls up at the elbow, and drains a jumper, troops be damned.

Coach Pace yanks him, jumps down his throat. “Don’t you ever pull up one-on-three again!”

A new fear infects Oli: the fear of limitations.

Luckily, a second teacher emerges on the blacktops of nearby Elm Avenue Town Park. Built like a running back, Valiant Prophet Robinson takes no shit, talks mad trash, moves with contagious swagger, soars through the air, welcomes all comers, and dominates the park’s two courts.

Oli wants nothing more than to catch Valiant’s eye. So, he watches, listens, learns. When Valiant does decide to take him under his wing, Oli has a hard time seeing why.

One day, Valiant is watching as Oli goes one-on-three in transition, then waits for his troops. Valiant ain’t having it; from the sidelines, he shrills: “Don’t slow up! You go at ’em! High school ball’s gonna ruin you! You gotta play with confidence out here!”

Within Oli, this teacher unlocks a new way of understanding basketball: If he is more Valiant, he’s free to explore his own skills and discover his strengths. He gets to figure out the best parts of his own game so he can understand how to make others better. He gets to take risks. He can play fearlessly.

Valiant Prophet Robinson opens Oli’s mind and helps him see what is possible. He teaches him how to sense the game and elevate his awareness above the competition.

A couple years later, though Oli is playing varsity ball, his visits to the park only increase. One evening, Valiant puts one arm around his protégé, then waves his free hand across the playground courts.

“See that,” Valiant tells Oli. “Someday, this will all be yours….”

Back in 2022, I am wondering what this story has to do with the topic I’ve called about: chess. Doc senses the question coming.

“So, you’ve seen ‘Searching for Bobby Fischer,’ right? Remember how there are two teachers? Well, Valiant—he was my Laurence Fishburne. He showed me that it was okay to bring out my queen.”

Doc loves relating chess to how humans think and how our brains work. As a teacher and director of athletics at a Massachusetts charter school, he would teach his underprivileged students chess so they could see how it links to basketball and to life: moving pieces around, responding, using visualization to filter all the options. He knew discovering those connections would transcend sports.

I ask Doc if he can recall his own first chess match.

“Well, I remember my dad teaching me how to play on this monster board my mother had given him one birthday,” he says. “It had these huge wood pieces. I think I just wanted to use the knights because they could jump. I was fascinated with how they could move differently. They didn’t just slide. They jumped and moved in an ‘L’. I thought, ‘That’s cool. They jump up and down—just like basketball players.’”

In his manuscript, Doc describes a strategy-planning session with a former assistant. Brainstorming ways they could out-prepare the competition, Doc posits that basketball resembles chess: “We want to imagine what they may do and then counter it by surprise attack or more efficient play. I said, ‘In chess, I’ll move here so that he moves here so that I can move there.’”

“‘Basketball isn’t chess,’” the assistant responds, but Doc knows he’s onto something. He writes:

Basketball is like chess, however, because it’s a constant give and take, pull and push of counters and counters to those counters. As a coach, I spend a great deal of time imagining and predicting what the opposite coach may do. I am out-dueling him in predictions, trying to one-up his revelations with my own higher-level revelation. I make an inference about his inference, and then another about that most recent one.

Doc highlights how the need to invent competitive edges brings chess and basketball even closer together. “But that assistant was right in a way,” the passage continues. “First off, chess is not as fast as basketball. You have prescribed openings and matching counters. And while you can do that in basketball, chess pieces don’t have personalities.”

Indeed, time and pace are no small factors. For instance, the International Chess Federation (FIDE) handbook for the 2022 Candidates Tournament prescribes time boundaries that shrink significantly after the first 40 moves.

Three concepts seem to dominate academic discussions on expert decision-making: visualization, pattern recognition, and search, which this Australian study defines as “generating and evaluating alternatives.” That same paper concludes that experts—in this case, chess grandmasters—are able to search more quickly and more thoroughly than intermediate players. They are better (and faster) at recognizing patterns because they’ve internalized more “chunks and templates.” In short, they’ve experienced (or considered) more situations, and that gives him them a clear edge over less-skilled players. Still, that edge is tethered to their specialization: Aside from chess, grandmasters, lack any inherent or identifiable intellectual advantage.

A joint study from researchers at Harvard and University of Arizona reports its group of grandmasters were 36.5 percent more likely to make a mistake in “rapid games” than in “classical games.” Additional time to think helped these grandmasters make “fewer and smaller mistakes” when they could see the board, but that extra time had no real influence on their ability to play speed chess, even blindfolded. (In fact, some blindfold players don’t even like to see an empty chess board because they think it interferes with their “visualization and analysis.”) Among the authors’ most compelling findings:

It seems clear that other, presumably higher-level processes must intervene between knowledge of patterns and selection of moves. These processes presumably involve associative factors and extensive search and evaluation. We suggest that visualization, perhaps along with some additional as yet unidentified higher-conceptual or representational techniques, may provide a neglected missing link.

My favorite fact actually appears in this paper’s first endnote, which describes how three world chess champions (Anatoly Karpov, Kasparov, and Vladimir Kramnik) jointly protested the FIDE decision to reduce the time limit of major tournament matches by approximately 50 percent: “The three grandmasters stated that ‘drastically shortening the amount of time available during a game is an attack on both the players and the artistic and scientific elements of the game of chess itself.’”

That smacks of fear to me: the fear of losing an edge. So if faster play and randomization can throw grandmasters off their game, how does that translate onto the hardwood?

“If we can manipulate things to fit a certain way, move some pieces around, mess with their schema, we can mess with other teams’ processing,” Doc explains. “If we present a formation they’ve never seen before, or run an action they’ve never seen before, there’s no way they can stop it [because] they’ve learned how to stop things based on situational cues. If we present cues they’ve never seen before, we’re going to score. Now, we might not score, or it might only work one time—still, that’s one possession where we frustrate and fluster them.”

I can sense Doc smiling when I ask him to go further. Everything about his voice says he loves this topic. It’s not just part of who he is as a coach; it’s part of what his mind finds fun. I can hear actual glee when I ask him how this angle has helped his once-ineffectual Caltech Beavers disrupt and defeat superior opponents. After all, they’ve beaten every conference opponent at least once since snapping their mammoth losing streak, even registering a 9-7 conference record in 2019-2020 that led to Southern California Intercollegiate Athletic Conference Coaching Staff of the Year honors.

“Most coaches aren’t going to change what they do,” Doc explains. “They have their plays. They have their strategy. They’re going to defend a certain way. So, we use that to their disadvantage and to our advantage.”

When I tell him it sounds like guerilla warfare, Doc chuckles.

“Yeah, we’re creating chaos and then utilizing that chaos to our advantage.”

In the movie, Josh succeeds by blending his teachers’ philosophies. Doc understands that a mix of by-the-book and outside-the-box approaches gives his team the best chances for success. After all, it’s Pandolfini (Kingsley) who wipes all the chess pieces off the board and tells Josh to imagine all the moves. Pandolfini’s methods help Josh turn structural fundamentals and visualization into winning strategy. In effect, he teaches Josh how to draw maps in his mind.

When he thinks of his high school coach now, Doc recognizes his value: He learned proper technique as well as how to acquire, develop, and maintain skills he would use while starring for Clark University. However, he also makes it clear that his high school coach showed him more of what not to do.

“When I started coaching, I realized I was just too immature then to understand all that. But I use any sort of data to help me as far as development. So, if someone’s doing something in a way that I don’t agree with, then I still use that as information to say, ‘Hey, that’s not the way I want to coach.’ But that is part of the reason I’ve evolved into someone so determined to be specific when it comes to teaching all of those things: The formal experiences have certainly made me a better coach.

“I was so intrinsically motivated to develop and get better and always searching, searching, searching for ways to understand the game and increase my competencies and my confidence at the same time. But I also wanted to be free, play free, and that’s why I sort of gravitated toward Valiant.”

Rigid adherence to a system wasn’t going to solve the quarter-century knot Doc had been hired to untangle. Wanting to revolutionize a program and their entire worldview, he had to get his players and his coaches to subscribe to his new, unorthodox approach. To begin, Doc boiled everything down to the most basic catalyst for human reaction: fear.

That first coast without training wheels, first plunge off the high dive, first climb up a roller coaster, first time shooting a crucial free throw.

“Everything comes down to survival, which is the reason we’re able to do mental imagery of anything. It allows us to prepare our bodies and minds for the next thing.”

Doc’s dissertation research brought him to Harvard professor Stephen Kosslyn, whose work has been dedicated to the science of learning and mental imagery. He credits Kosslyn for helping him formulate many of his own ideas.

“We want to teach our guys how to self-regulate, how to be very self-aware without overthinking and overanalyzing,” Doc explains. “We want them to enter a state of flow. Being able to move through a really fast game—a lot of it is how you overcome stress and overcome fear. The brain can’t decipher between mental rehearsal and physical practice: It fires almost the exact way as it would when you’re doing an actual task. So, if I’m shooting a free throw and you hook me up to a scan, you would see certain parts of the brain lighting up in the primary motor cortex and the somatosensory cortex (among other parts of the brain used for planning). The same areas are activated when you imagine shooting a free throw, even though you’re not doing the physical part.”

In the end, everything is about embracing stress and regulating fear in the moment.

“Stress and fear are there to say, ‘Hey, something’s up here. I’ve got to figure out how to navigate the situation.’ So instead of running from it, the best thing to do is embrace it so you’re then able to adapt and self-regulate, and embrace that adversity.”

Doc does anticipation training to expand beyond visualization into mental imagery, which involves all the senses. Doc wants his players not only to see the game in real time, but also to touch, taste, smell, and hear it as they do.

“This is why pickup basketball is so incredible,” Doc says. “To be effective, you have to create quick mental maps and anticipate how the other four players on your team are going to react. You don’t know them at all, so movements and reactions are based on what you think they are going to do—based on what you’ve observed other players doing in the past—but could be totally different.”

Doc bases much of his philosophy on complexity theory—or the idea that nothing is stable.

“If I’m working with a team, I want us to live at the edge. Most people stand at the edge and they’re scared of what might happen. But we want to have the mentality that we’re standing at the edge of chaos—we want to utilize that chaos to make us better.”

(Go back and watch that opening clip!)

In an effort to mitigate that chaos, many coaches will cling to systematic control. However, blind devotion to system can easily turn into a form of stasis that renders teams susceptible to prediction. Plus, dogmatic worship of X’s and O’s tends to put all accountability on the players.

“When a play doesn’t work or a system breaks down, there’s just going to be a lot of blame,” Doc says, “and that’s going to turn into disloyalty because you end up playing favorites with certain players.”

Thus, a chess-playing basketball coach—in order to use all of his pieces in combination to attack (or defend)—must first appreciate that teaching methods might have to adjust.

“There are going to be a lot of adaptations and challenges along the way—it’s not all smooth. So, you have to have an open mind to working with new people and figuring out how to create some consistency and sustainability. But there’s always chaos at some point. Coaches might feel like everything’s moving really well. You have a good month or whatever. But at some point, you want there to be chaos because only through chaos do you get to the next level.”

I wonder aloud why more coaches in NBA organizations aren’t doing this, especially considering the long-term fiscal advantages of maximizing your in-house potential.

“Coaches are in a rush to win. In the NBA—unless you’re tanking for draft picks or in a complete rebuild—you’ve got to win. Otherwise, you’re going to get fired because a lot of owners don’t have patience. So that’s a real barrier [to teaching] in pro sports.”

From a teaching perspective, though, the chess mindset is more about keeping an open mind and fueling a willingness to learn. In fact, one of Doc’s mantras is: “Learn more and keep learning.”

In “Searching for Bobby Fischer,” Vinnie teaches Josh to feel the game, to play free, take risks, and trust his burgeoning skills; Pandolfini teaches him the importance of control and visualization. Both have the same goal—to get their pupil to the point where he can handle any situation—and eventually, the film vindicates both approaches when Josh uses a combination of their methods to defeat a vaunted wunderkind.

That teaching goal should be the same in basketball, but a white-knuckle grip on one system or method will hold coaches back. Doc’s high school coach may have taught him how to recognize patterns, but Valiant Prophet Robinson uncovered how to take that edge away from the competition by “bringing out his queen” and creating chaos.

By embracing that chaos, as Doc has, coaches can help players mentally prepare for greater variables. The more situations players have been in, the better they’ll be able to filter all the possible responses, then decide how to react—all in the microseconds of real time.

Eureka!

Thank you for reading TrueHoop!